فولاد Wootz ، گلدار کردن فولاد منحصر به فرد و بسیار باارزش در شبه قاره هند در اوایل قرن 5 قبل از میلاد ایجاد شده است. خواص آن منحصر به فرد است به دلیل ذوب خاص و بازسازی از فولاد بعلت ایجاد شبکه های کاربید آهن کروی در یک ماتریس از پرلیت. استفاده از فولاد گلدار در شمشیر در قرون 16 و 17 بسیار محبوب شد.تاریخ فولاد دمشقی و ایرانی و هندی از این فولاد گرفته شده است.

جهت کسب اطلاعات بیشتر به ادامه مطلب مراجعه نمایید

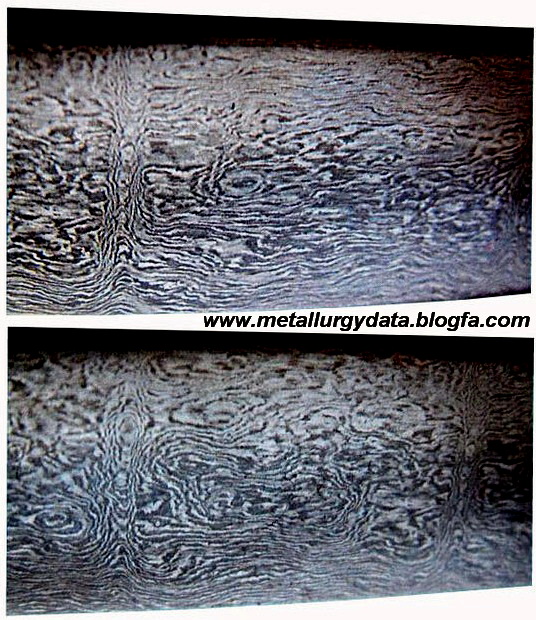

Wootz steel is a steel characterized by a pattern of bands or sheets of micro carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix. It is stated to have developed in India around 300 BC.

The word wootz may have been a mistranscription of wook, an anglicised version of urukku (உருக்கு) (ഉരുക്കു), the word for melting in Tamil and Malayalam or urukke, the word for steel in Kannada (ಉರ್ಕು, ಉಕ್ಕು), Telugu (ఉక్కు) and many other Dravidian languages.

History

According to traditional history wootz steel originated in India in the 3rd century BCE. There is archaeological evidence of the manufacturing process in South India from that time. Wootz steel was widely exported and traded throughout ancient Europe and the Arab world, and became particularly famous in the Middle East, where it was known as Damascus steel.

In ancient times, thirty pounds of steel was a precious gift, deemed by King Porus worthy of presentation to Alexander the Great. Another sign that Ancient India was celebrated for its steel is seen in a Persian phrase — to give an "Indian answer," meaning "a cut with an Indian sword."

Wootz steel and development of modern metallurgy

Legends of wootz steel and Damascus swords aroused the curiosity of the European scientific community from the 17th to the 19th Century. The use of high carbon alloys was not known in Europe previously and thus the research into wootz steel played an important role in the development of modern English, French and Russian metallurgy.

Extant examples

In 1790, samples of wootz steel were received by Sir Joseph Banks, President of the British Royal society, sent by Helenus Scott. These samples were subjected to scientific examination and analysis by several experts.

Specimens of daggers and other weapons were sent by the Rajahs of India to the International Exhibition of 1851 and 1862. Though the arms of the swords were beautifully decorated and jeweled, they were most highly prized for the quality of their steel. The swords of the Sikhs were said to bear bending and crumpling, and yet be fine and sharp.

Characteristics

Wootz is characterized by a pattern caused by bands of clustered Fe

3C particles made of microsegregation of low levels of carbide-forming elements. There is a possibility of an abundance of ultrahard metallic carbides in the steel matrix precipitating out in bands. Wootz swords, especially Damascus blades, were renowned for their sharpness and toughness.

Steel manufactured in Kutch particularly enjoyed a widespread reputation, similar to those manufactured at Glasgow and Sheffield.

The techniques for its making died out around 1700. According to Sir Richard Burton the British prohibited the trade in 1866:

About a pound weight of malleable iron, made from magnetic ore, is placed, minutely broken and moistened, in a crucible of refractory clay, together with finely chopped pieces of wood Cassia auriculata. It is packed without flux. The open pots are then covered with the green leaves of the Asclepias gigantea or the Convolvulus lanifolius, and the tops are coated over with wet clay, which is sun-dried to hardness. Charcoal will not do as a substitute for the green twigs. Some two dozen of these cupels or crucibles are disposed archways at the bottom of a furnace, whose blast is managed with bellows of bullock's hide. The fuel is composed mostly of charcoal and of sun-dried brattis or cow-chips. After two or three hours' smelting the cooled crucibles are broken up, when the regulus appears in the shape and size of half an egg. According to Tavernier, the best buttons from about Golconda were as large as a halfpenny roll, and sufficed to make two Sword-blades . These 'cops' are converted into bars by exposure for several hours to a charcoal fire not hot enough to melt them : they are then turned over before the blast, and thus the too highly carburised steel is oxidised. According to Professor Oldham, 'Wootz' is also worked in the Damudah Valley, at Birbhum, Dyucha, Narayanpur, Damrah, and Goanpiir. In 1852 some thirty furnaces at Dyucha reduced the ore to kachhd or pig-iron, small blooms from Catalan forges; as many more converted it to steel), prepared in furnaces of different kind. The work was done by different castes ; the Moslems laboured at the rude metal, and the Hindu preferred the refining work. I have read that anciently a large quantity of Wootz found its way westward via Peshdwar.When last visiting (April 19, 1876) the Mahabaleshwar Hills near Bombay, I had the pleasure to meet Mr. Joyner, C.E., and with his assistance made personal inquiries into the process. The whole of the Sayhddri range (Western Ghats), and especially the great-Might-of-Shiva mountains, had for many ages supplied Persia with the best steel. Our Government, since 1866, forbade the industry, as it threatened the highlands with disforesting. The ore was worked by the Hill-tribes, of whom the principal are the Dhdnwars, Dravidians now speaking Hindustani. Only the brickwork of their many raised furnaces remained. For fuel they preferred the Jumbul-wood, and the Anjan or iron-wood. They packed the iron and fourteen pounds of charcoal in layers ; and, after two hours of bellows-working, the metal flowed into the forms. The Kurs' (bloom), five inches in diameter by two and a half deep, was then beaten into Tdwds or plates. The matrix resembled the Brazilian, a poor yellow-brown limonite striping the mud-coloured clay; and actual testing disproved the common idea that the 'watering' of the surface is found in the metal. The Jauhar, 'jewel' or ribboning) of the so-called Damascus' blade was produced artificially, mostly by drawing out the steel into thin ribbons which were piled and welded by the hammer. Oral tradition in India maintains that a small piece of either white or black hematite (or old wootz) had to be included in each melt, and that a minimum of these elements must be present in the steel for the proper segregation of the micro carbides to take place.